". . . I am not free from a tendency to see in this fate some special, unparalleled tragedy, although I know that other peoples have had to bear the burden of wishing the defeat of their nation for its own good and for the sake of a shared future."

Thomas Mann

Thursday, October 30, 2008

The cities of Europe have burned before, and they may yet burn again.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

The Horror Genre

Chartered by the BFI in conjunction with the BBC's award-winning Spinechillers radio series, The Horror Genre by Paul Wells purports itself as a primer for those beginning film studies and who are interested in the horror film specifically. This is problematic from the start: Film is rarely taken seriously enough and the horror genre is rarely taken seriously - add to this the fact that academic film studies are rarely more than a soft option for those looking to become grips in Hollywood and the study of horror films becomes downright laughable. This book is no exception.

purports itself as a primer for those beginning film studies and who are interested in the horror film specifically. This is problematic from the start: Film is rarely taken seriously enough and the horror genre is rarely taken seriously - add to this the fact that academic film studies are rarely more than a soft option for those looking to become grips in Hollywood and the study of horror films becomes downright laughable. This book is no exception.

Like most film study I've read, The Horror Genre looks at film through the same lens as literature, breaking it down into the same generic movements and assuming the same generic influences. It assumes that horror films are social documents, merely reflecting the values of their time. The book makes little mention of the obvious stars of the show. In fact, it spends as much time on the genre's darling, Psycho, as it does on Batman Returns - a movie wholly outside the genre. It is content to lay down a timeline, to delineate the major themes outside of film during those times, and to list the films which were made inside those times. It suggests two major movements in horror - 1919-1960 ("Consensus and Constraint") and 1960-2000 ("Chaos and Collapse") and touches briefly on the major studio movements, which are key to understanding the evolution of horror. The first thirty-three pages are wasted on sophomoric name-dropping and attempts to legitimize the very idea of horror-study by tying it to such concepts as Marxism, Darwinism, and Symbolism and such visionaries as Nietzsche and Bataille. Those pages are practically unreadable. The remaining book is a breathless exhibition as the author stumbles to provide as many movie titles into his forcedly-fluid timeline as possible. I feel sorry for the undergraduate whose course is assembled around this sorry state of affairs.

But there is something there. Something to study and discuss in the horror film that transcends the baseness of social comment and enters into the primeval world of symbols and archetypes - of God and art. There is something that speaks to meaning inside all of us, and there are horror films which are capable of disturbing, terrifying, and opening up our eyes to the very things which keep us from communicating with each other, from living with one another.

I remember in school when we first learned about the literary device of conflict and how it was generally broken down into simple dualities - man vs. nature, man vs. God, man vs. man, man vs. himself. When I first saw A Picnic at Hanging Rock - one of the best horror films ever made, in my estimation - I was shocked by the realization that none of these dualities were real. They were simple extensions of the one true conflict, man vs. the other. There is no way in Picnic to define what happened on the rock, who the enemy was, if there was one. There is little proof there, even, that we are who we are. There are vague impressions of what it is to be human, the soft-fleeting juxtaform of memory, but when the limits of that experience are reached there is terror in the face of the barrier.

Last night a friend told me that he awoke recently to find a book, which he'd left on his bed, levitating. This terrified him, because he knew that it was impossible. And that is what terror is: to be confronted with something against which your knowledge of the world can provide no traction. In that definition, there is so much available for the genre to play with, but I must confess myself disappointed with both it and the study of it.

Like most film study I've read, The Horror Genre looks at film through the same lens as literature, breaking it down into the same generic movements and assuming the same generic influences. It assumes that horror films are social documents, merely reflecting the values of their time. The book makes little mention of the obvious stars of the show. In fact, it spends as much time on the genre's darling, Psycho, as it does on Batman Returns - a movie wholly outside the genre. It is content to lay down a timeline, to delineate the major themes outside of film during those times, and to list the films which were made inside those times. It suggests two major movements in horror - 1919-1960 ("Consensus and Constraint") and 1960-2000 ("Chaos and Collapse") and touches briefly on the major studio movements, which are key to understanding the evolution of horror. The first thirty-three pages are wasted on sophomoric name-dropping and attempts to legitimize the very idea of horror-study by tying it to such concepts as Marxism, Darwinism, and Symbolism and such visionaries as Nietzsche and Bataille. Those pages are practically unreadable. The remaining book is a breathless exhibition as the author stumbles to provide as many movie titles into his forcedly-fluid timeline as possible. I feel sorry for the undergraduate whose course is assembled around this sorry state of affairs.

But there is something there. Something to study and discuss in the horror film that transcends the baseness of social comment and enters into the primeval world of symbols and archetypes - of God and art. There is something that speaks to meaning inside all of us, and there are horror films which are capable of disturbing, terrifying, and opening up our eyes to the very things which keep us from communicating with each other, from living with one another.

I remember in school when we first learned about the literary device of conflict and how it was generally broken down into simple dualities - man vs. nature, man vs. God, man vs. man, man vs. himself. When I first saw A Picnic at Hanging Rock - one of the best horror films ever made, in my estimation - I was shocked by the realization that none of these dualities were real. They were simple extensions of the one true conflict, man vs. the other. There is no way in Picnic to define what happened on the rock, who the enemy was, if there was one. There is little proof there, even, that we are who we are. There are vague impressions of what it is to be human, the soft-fleeting juxtaform of memory, but when the limits of that experience are reached there is terror in the face of the barrier.

Last night a friend told me that he awoke recently to find a book, which he'd left on his bed, levitating. This terrified him, because he knew that it was impossible. And that is what terror is: to be confronted with something against which your knowledge of the world can provide no traction. In that definition, there is so much available for the genre to play with, but I must confess myself disappointed with both it and the study of it.

Monday, October 20, 2008

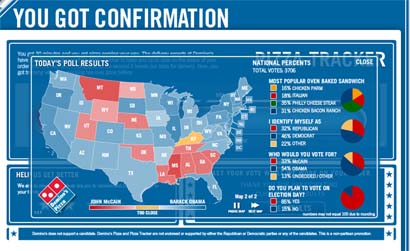

Election '08

Thursday, October 16, 2008

I Brake For Boiled Peanuts

I grew up eating boiled peanuts. My mother spent a brief period in Florida before I was born, which is where I think she discovered the little jewels and smuggled them up to the cutting edge of the Mason-Dixon line. Rutters mini-marts carried them up until I was in middle school but after they stopped the boiled peanut made a sad exit from my life for many years.

In 2004 Anna took a trip to visit her daughter in Georgia and brought back boiled peanuts at my request. They were heavenly - everything I remembered. I simply had to have more, but, while managing a grocery store gives me transcendent food-sourcing abilities, it wasn’t until Wegmans moved into Maryland that a grocery store here offered them - not even the Carolina-based Food Lion. Millbrook, Weis’ then-gourmet vendor, could not source them, and our produce buyers flat-out refused to purchase in-shell raw peanuts. So I finally turned to the internet for help.

It’s odd that I took so long to look to the internet for boiled peanuts. I made my first webpage in 1995 and I bought my first domain in 1996. I was on the #html channel on DALnet back before Michelle from SapphireBlue.com married Don from RatBastard.org. I am so old school. But I freak out when I can’t find cruelty-free shampoo within a twenty minute drive, and I go without boiled peanuts for years when the local grocer can’t get them. Such is life.

Naturally my search for boiled peanuts led me to http://www.boiledpeanuts.com where I discovered the Lee Bros, who make their living selling the South to disenfranchised southerners and - as their cookbook title suggests - “would-be” southerners. Their website is a plethora of southern foods, from grits to pickled peaches, and I was absolutely amazed by it. I ended up buying my boiled peanuts elsewhere, because the Lees sell theirs frozen which makes shipping expensive, but I vowed to return.

It wasn’t until I saw Anthony Bourdain’s Charleston, SC episode of No Reservations - which featured the Lees heavily - that I actually did return and purchased their cookbook. Since then I have made the following recipes from it:

- Lee Bros. Sweet Tea

How do you get away with a recipe for sweet tea? Mix 150 parts sugar to 1 part tea. Done. But their recipe uses a simple syrup versus plain sugar, which I find to be an elegant solution.

- Mint Simple Syrup

My grandmother had huge patches of mint at her house and we all grew up on mint tea. The smell of it steeping in the summer kitchen is one of my favorite memories of childhood. I miss my grandmother so, so much and the first taste of mint-infused sweet tea using the recipe in this book almost made me cry. I’ve tried a few variations on this, including raspberry and mango syrups, but I really do prefer the mint. The coolest thing is this: make a pitcher of regular tea, unsweetened, and keep a couple jars of variously flavored syrups handy. Mint tea, sweet tea, mango tea - they’re all just a tablespoon away.

- Edamame

Ok, so I made this before I bought the cookbook - but how savvy of those crafty Southerners to be hip to edamame. Heck, even my MS Word isn’t in-the-know.

- Coleslaw

A decent recipe that does away with blanching the cabbage, resulting in a nice peppery finish. The second time around I opted for a straight-up dill relish instead of the “not too sweet” sweet relish the recipe requests. It makes a nice difference.

- Matt’s Honey-Glazed Field Peas

I had to ask my Goya rep to bring in a case of cow peas especially for me to make this recipe. The two bags I bought - back on the fourth of July - remain the only two we’ve sold. I replaced the country ham in this recipe with a vegetarian ham I bought at Roots Market and an absolutely glittering Tupelo honey from Wegmans. The result was a smoky, rich baked bean that was so much better than any baked bean I’ve ever had. But, to be honest, I wouldn’t mind using a larger bean next time around.

- Shrimp Burgers (for my dad on Father’s Day)

A note for vegetarians trying to make shrimp for their father: if the recipe calls for you to steam the shrimp until pink, don’t start off with pink Gulf shrimp. I paired these up with the aforementioned coleslaw for Dad, who in his typically detached, Eeyore-esque way said “Thanks.”

- Sweet Potato Buttermilk Pie

This pie is incredible. The Lee Bros said they created the recipe as a reaction to the typically leaden Sweet Potato pie and in that light this is a revelation. It easily trumps even the best of pumpkin pies. The crust is great, although it calls for lard, so I had to substitute shortening. I want to try exchanging the sweet potato for pumpkin.

- Sorghum Pecan Pie

The sorghum syrup which binds this pie together has a nice hearty tang to it that is dimly reminiscent of tomatoes. It wasn’t the smash hit that the Sweet Potato pie was because of that, I think. Today’s Pecan Pie is a high fructose corn syrup monstrosity that overwhelms the earthy flavor of the nuts with its sweetness, which provides nothing else in terms of taste.

- Red Velvet Cake

I was so excited about these. Big, fluffy red velvet cupcakes with cream cheese icing, all from scratch. Despite growing up with my Depression-era Grandmother, who had an affinity for homemade icings, I had never had a homemade cake before. I expected it to be superior to box cakes in all ways: lighter, sweeter, more tender. The result required a little introspection, because I hated it at first. The cake was dry and leaden, the superfluity of red food coloring felt wrong - like that green chocolate syrup Hershey’s came out with during the release of The Hulk. The Lee Bros recipe uses the zest from two oranges and cocoa powder which results in a very orangey sort of chocolate. In the future I am considering making the chocolate one of the liquid ingredients and reducing the orange zest.

- Bird-head Buttermilk Biscuits

Underwhelming. I added 1/3c. Extra sharp cheddar cheese to the recipe which had the effect of cancelling the buttermilk’s tang while not imparting any cheese flavor whatsoever. The worst of both worlds!

In addition to great recipes The Lee Bros cookbook is a treasure chest of stories from the brothers’ past which are very enjoyable. I recommend it wholeheartedly. I plan on buying the “Charleston Receipts” cookbook from their website as well, which will hopefully be a deeper dive into Appalachia. Until then, The Lee Bros. Southern Cookbook: Stories and Recipes for Southerners and Would-be Southerners

Monday, October 13, 2008

We Never Make Mistakes

I own virtually everything Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn ever wrote.

His books have decidedly catchy names like We Never Make Mistakes and Warning to the West that draw me to them at used (and not so used) bookstores and opening phrases and paragraphs that make them go back to the bookshelf.

. . .

I’ve never read him. Until now.

We Never Make Mistakes consists of two short stories, brought together for the English speaking world in 1963 by the University of South Carolina and translated by Paul W. Blackstock. It’s the only translation you’ll find, so far as I can tell, and it’s passable with minor exceptions. There are definite issues with reading Russian that footnotes could probably help. For instance, the main character in An Incident at Krechetovka Station is named Lieutenant Vasya Zotov, but he is consistently referred to as Vasili Vasilitch. While I’m not entirely sure why, it seems that it must be some sort of diminutive or nickname, but he’s referred to as this by his civilian counterparts who also refer to him as Sir. Furthermore, the translator assumes that such abbreviations as NKVD will be familiar to the reader while making a similar assumption that NKPS will not be. Assuming this in 1963 was probably not a horrible idea, and maybe I should be more aware of my surroundings when jumping into prison camp literature; however, my edition was re-released in 2003 and is a re-release of a 1996 edition: the NKVD, or People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, was renamed the MVD in 1946. Given that the average high school student no longer knows what the sickle and hammer stand for, a footnote seems in order. My edition of Gogol’s Dead Souls, by comparison, had so many footnotes that I felt as if I were reading Joyce.

consists of two short stories, brought together for the English speaking world in 1963 by the University of South Carolina and translated by Paul W. Blackstock. It’s the only translation you’ll find, so far as I can tell, and it’s passable with minor exceptions. There are definite issues with reading Russian that footnotes could probably help. For instance, the main character in An Incident at Krechetovka Station is named Lieutenant Vasya Zotov, but he is consistently referred to as Vasili Vasilitch. While I’m not entirely sure why, it seems that it must be some sort of diminutive or nickname, but he’s referred to as this by his civilian counterparts who also refer to him as Sir. Furthermore, the translator assumes that such abbreviations as NKVD will be familiar to the reader while making a similar assumption that NKPS will not be. Assuming this in 1963 was probably not a horrible idea, and maybe I should be more aware of my surroundings when jumping into prison camp literature; however, my edition was re-released in 2003 and is a re-release of a 1996 edition: the NKVD, or People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, was renamed the MVD in 1946. Given that the average high school student no longer knows what the sickle and hammer stand for, a footnote seems in order. My edition of Gogol’s Dead Souls, by comparison, had so many footnotes that I felt as if I were reading Joyce.

The two shorts stories in We Never Make Mistakes are An Incident at Krechetovka Station and Matryona’s House. The second is considerably better than the first - so for now I’ll concentrate on the first.

An Incident… deals with the aforementioned Lt. Zotov and his workaday life at the Krechetovka train station during WWII. Zotov is a very young man, desperately patriotic, who longs to be on the front lines, but who is reduced to receiving coded messages and arranging for train departures and arrivals. He does not understand the things that are happening in his country: there have been conflicting reports as to where the front lies and his job entitles him to information that conflicts these reports even more. The Germans are winning. They will take Moscow. His country will fall. But here he sits, trying to keep starving peasant’s from stealing sacks of flour from the trains. The world has yet to stop, despite the fact that it is crumbling.

The beginning of the story is nearly a landscape with very little in the way of plot or development, and when the story actually begins it does so with a haphazard pace that catches up with itself all-too-quickly. I truly enjoyed the images that the beginning imparted and you get a very definite sense of Solzhenitsyn’s deep patriotism from them: I could probably have read an entire story of nothing but Zotov going back and forth, sending out trains, pulling his blinds down, and listening in to nearby conversations. Alas, this was not to be. The story had an agenda - a message. Zotov was to portray the idea of Solzhenitsyn’s great struggle between his hatred of communist Russia and his love of his homeland. Zotov cannot deliver this message, though, because you are utterly detached from him. You are meant to feel Zotov’s pain at being kept from the front, at his estrangement from his family, at his loneliness. You are meant to feel the helplessness of his situation and - perhaps - the pointlessness of his plight. But not, in any way, the pointlessness of his life.

The tale is, largely, autobiographical as most of Solzhenitsyn’s works are. As a younger man he never questioned party politics and was, like Zotov, completely content to read Das Kapital. Both men were well educated and sought out enlightenment after their schooling had ended. Both of their lives revolved around numbers. Both men eventually lost their faith in the party: Solzhenitsyn’s dissolving moment being the eight years he spent in the gulag. Yet I’m reminded of Elie Wiesel, who makes absurd amounts of money publicizing his pain and suffering, all in the name of reminding the world about the atrocities that befell him and countless others. BUT. Both Wiesel and Solzhenitsyn survived their atrocities and in considerably more comfort (both then and now) than most of their fellows and both now sit back in comfort (...or death) and reminisce about their experiences, gaining accolades and awards (honorary doctorates, even) and praise left and right. Introspection and a third-person point of view seem almost wrong in the face of such atrocities. And let’s face it: Solzhenitsyn really doesn’t have anything to say about the banality of evil which allows man to sit idly by while gulags exist. He has nothing to say about the evil in all men that makes them long for the suffering of others. He has nothing to say about the good in man that can rise above the worst in God. He has only this to say: Soviet Russia was disinheriting and awful. It brought low an idyllic people. Zotov’s pain and frustration is remote because he has utterly polarized the world into a party that he must love because it comes from Russia and a Russian past which is perfect and yet at odds with its present. This romantic notion of Russia past is so childlike that we can hardly accept the idea that Zotov could come to terms with a struggle between the party and that past. Solzhenitsyn, we can be sure, never did. He blamed the October Revolution on the Jews and continued on adoring the past which they fractured.

Harvard Professor Richard Pipes says this of Solzhenitsyn:

His books have decidedly catchy names like We Never Make Mistakes and Warning to the West that draw me to them at used (and not so used) bookstores and opening phrases and paragraphs that make them go back to the bookshelf.

“Hello. Is this the dispatcher?”

“Well?”

“Who is this? Dyachichin?”

“Well?”

“Don’t ‘well’ me - I said, are you Dyachichin?”

“Drive the tank car from track seven to three. Yes, I’m Dyachichin.”

“This is the Army Commandant’s aide, Lieutenant Zotov, speaking! Listen, what’re you doing up there? Why haven’t you dispatched the echelon to Lipetsk before this? Number 67 - uh - what’s the last number, Valya?”

. . .

I’ve never read him. Until now.

We Never Make Mistakes

The two shorts stories in We Never Make Mistakes are An Incident at Krechetovka Station and Matryona’s House. The second is considerably better than the first - so for now I’ll concentrate on the first.

An Incident… deals with the aforementioned Lt. Zotov and his workaday life at the Krechetovka train station during WWII. Zotov is a very young man, desperately patriotic, who longs to be on the front lines, but who is reduced to receiving coded messages and arranging for train departures and arrivals. He does not understand the things that are happening in his country: there have been conflicting reports as to where the front lies and his job entitles him to information that conflicts these reports even more. The Germans are winning. They will take Moscow. His country will fall. But here he sits, trying to keep starving peasant’s from stealing sacks of flour from the trains. The world has yet to stop, despite the fact that it is crumbling.

The beginning of the story is nearly a landscape with very little in the way of plot or development, and when the story actually begins it does so with a haphazard pace that catches up with itself all-too-quickly. I truly enjoyed the images that the beginning imparted and you get a very definite sense of Solzhenitsyn’s deep patriotism from them: I could probably have read an entire story of nothing but Zotov going back and forth, sending out trains, pulling his blinds down, and listening in to nearby conversations. Alas, this was not to be. The story had an agenda - a message. Zotov was to portray the idea of Solzhenitsyn’s great struggle between his hatred of communist Russia and his love of his homeland. Zotov cannot deliver this message, though, because you are utterly detached from him. You are meant to feel Zotov’s pain at being kept from the front, at his estrangement from his family, at his loneliness. You are meant to feel the helplessness of his situation and - perhaps - the pointlessness of his plight. But not, in any way, the pointlessness of his life.

The tale is, largely, autobiographical as most of Solzhenitsyn’s works are. As a younger man he never questioned party politics and was, like Zotov, completely content to read Das Kapital. Both men were well educated and sought out enlightenment after their schooling had ended. Both of their lives revolved around numbers. Both men eventually lost their faith in the party: Solzhenitsyn’s dissolving moment being the eight years he spent in the gulag. Yet I’m reminded of Elie Wiesel, who makes absurd amounts of money publicizing his pain and suffering, all in the name of reminding the world about the atrocities that befell him and countless others. BUT. Both Wiesel and Solzhenitsyn survived their atrocities and in considerably more comfort (both then and now) than most of their fellows and both now sit back in comfort (...or death) and reminisce about their experiences, gaining accolades and awards (honorary doctorates, even) and praise left and right. Introspection and a third-person point of view seem almost wrong in the face of such atrocities. And let’s face it: Solzhenitsyn really doesn’t have anything to say about the banality of evil which allows man to sit idly by while gulags exist. He has nothing to say about the evil in all men that makes them long for the suffering of others. He has nothing to say about the good in man that can rise above the worst in God. He has only this to say: Soviet Russia was disinheriting and awful. It brought low an idyllic people. Zotov’s pain and frustration is remote because he has utterly polarized the world into a party that he must love because it comes from Russia and a Russian past which is perfect and yet at odds with its present. This romantic notion of Russia past is so childlike that we can hardly accept the idea that Zotov could come to terms with a struggle between the party and that past. Solzhenitsyn, we can be sure, never did. He blamed the October Revolution on the Jews and continued on adoring the past which they fractured.

Harvard Professor Richard Pipes says this of Solzhenitsyn:

Soviet Russia produced some of the strongest artists ever to walk this earth - but I fear that Solzhenitsyn’s fame in the West comes more from his rejection of Soviet Russia during the Cold War than from any actual merit of his own. The best that I can say of him is that he may be historically significant.

"Solzhenitsyn blamed the evils of Soviet communism on the West. He rightly stressed the European origins of Marxism, but he never asked himself why Marxism in other European countries led not to the gulag but to the welfare state. He reacted with white fury to any suggestion that the roots of Leninism and Stalinism could be found in Russia’s past. His knowledge of Russian history was very superficial and laced with a romantic sentimentalism. While accusing the West of imperialism, he seemed quite unaware of the extraordinary expansion of his own country into regions inhabited by non-Russians. He also denied that Imperial Russia practiced censorship or condemned political prisoners to hard labor, which, of course, was absurd."

Sunday, October 12, 2008

. . . they're mostly made of people.

"Turning and turning in the widening gyreIs there a more cliché way to start a blog than with Yeats?

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity."

We have lost our way. . . . I have lost my way. I want it back.

I used to read. I used to write. I used to save up every penny to buy incredibly expensive Criterion DVDs that I would watch over and over and over again, falling asleep to the commentary, writing essays. I miss that. Maybe. Just maybe this will help.

I enjoy film, literature, music, cooking. I plan on writing about all of these things.

Thanks for reading!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)